Director & Producer: Tracey Moffat (1987)

Length: 16:22

Link to Watch the Film: https://vimeo.com/201245792

Keywords: Political; Social Commentary; Colonization; Racism; Sexism; Experimental; Avant-Garde; Australian Aboriginal Women; Indigenous Film; Female Filmmaker

Tracey Moffat’s impactful first short film, carrying the tongue-in-cheek title of Nice Coloured Girls (1987), uses juxtaposition, opposition, and experimental film techniques to comment on the historical sexualization of Aboriginal women in Australia. As an Aboriginal Australian herself, Moffat provides a unique insider perspective that reimagines stereotypical representations of Aboriginal women as oppressed, passive, or lecherous. Indeed, in an interview in 1988, Moffat said her work is experimental in that “it is challenging previous styles of representation of Aborigines in film” (Moffat, 1988, p. 155). In this film, Moffat contrasts a modern fictional storyline with real historical accounts from white male colonizers during early contact, constructing a continuous narrative of the relationship between Aboriginal women and white men from past to present. However, Moffat defies the conventional linear form of the cinematic storyline, instead consistently interrupting the narrative with snapshots relating to the colonial history that provides a backdrop to the film, as well as anti-realist avant-garde imagery. The film masterfully brings together both the continuous and contradictory elements of gendered Aboriginal-colonial relations, both capturing and constructing the raw and enigmatic reality of this complex issue.

between white men and Aboriginal women.

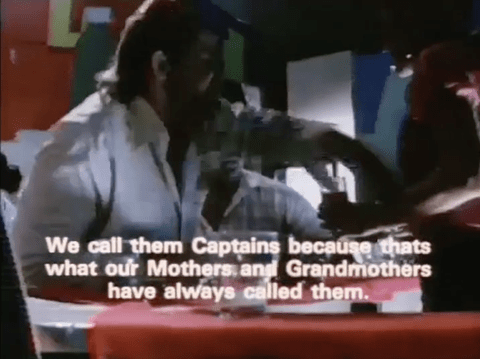

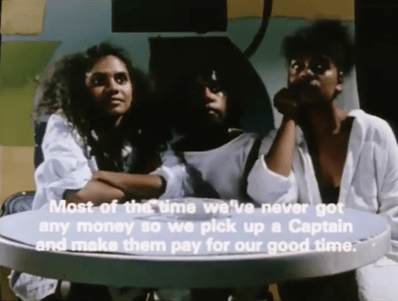

The main storyline threading the film together is based on a fictional narrative, but one that Moffat says “is a very real thing” (Moffat, 1988, p. 152). The film follows three Aboriginal women in the urban landscape of Sydney who exploit a drunk white man called a “Captain” to obtain drinks, food, and money on a night out. The scenes of this particular narrative are imbued with a sort of raw authenticity, likely reflective of Moffat’s intimacy with the subject, as she states “I used to do it, I used to do it with my sisters” (Moffat, 1988, p. 152).

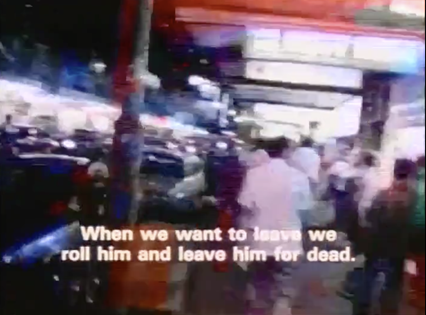

This story of contemporary Aboriginal women stealing from a white male ‘Captain’ seems in direct opposition with the voiceovers included in the film. A male voice reads direct excerpts from the journals of colonizers who encountered Australian Aboriginal people in the late 18th century. These men referred to the women as “flirtatious” and “wonton,” insinuating they used deceit and feminine wiles to lure in white men, while at times also victimizing, sexualizing, and patronizing these women. As Senzani (2007) points out in her analysis of the film, the voiceover is “reminiscent of colonial ethnographic films” (p. 53). Yet, the women in the film rely on the colonial construction of Aboriginal women as highly sexual and ‘nice,’ purposefully catering to the white, male, colonial gaze, in order to take advantage of a white male colonizer (Senzani, 2007, p. 54). In this way, Moffat simultaneously traces the narrative of Aboriginal women from past to present and successfully turns traditional and problematic colonial ethnography on its head. Moffat carefully portrays Aboriginal women, not simply as a dichotomy of oppressed in the past and empowered in the future, but as agents who embody both traits in complex ways. In the concluding scene, the women steal the Captain’s wallet and run off gleefully, at once a representation of both Aboriginal women’s marginalization and resilience.

drunk Captain’s wallet and run to find a cab.

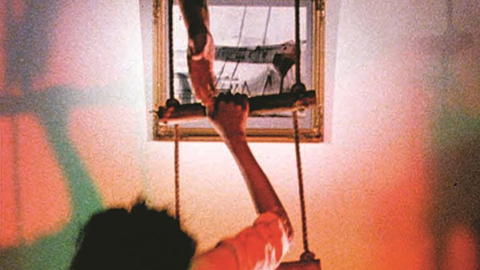

While the overarching theme of racism, sexism, and colonization that permeates the film is made most clear through contrasting modern imagery with archival material, Moffat uses experimental techniques in nuanced ways to increase the impact of the film on the viewer. For instance, while typical films might portray Aboriginal peoples ‘on the land’ and in rural settings, Moffat defies these expectations by focusing on a bustling urban environment. Sounds of someone rowing, waves, and seabirds represent a colonial soundscape, clashing with the modern raucous of the urban centre. Moffat further plays with ideas of setting by using framed paintings depicting early colonial landscapes in Australia, which are ultimately shown being destroyed.

Moffat’s use of avant-garde imagery to break up the storyline serves as a technique to keep the viewer engaged and thoughtful without getting lost purely in the narrative. Images of seemingly-random content often flash across the screen, calling the viewer to look for connections and ask questions about the film. This artistic quality is commented on by Moffat herself, who attributes her use of anti-realism to an attempt to break free of traditional realist narratives of POC. On the technique of using art installation and artificiality, Moffat says “I’m not concerned with capturing reality, I’m concerned with creating it myself” (Moffat, 1988, p. 155).

in front, alongside shadows and flashing coloured lights,

Nice Coloured Girls (1987) does not adhere to cinematic conventions of narrative, and therefore, it does not tie everything up in a neat little bow. Instead, Moffat’s social commentary, paired with experiential film techniques, urges us as an audience to engage with the material and explore the complexity of Aboriginal women’s lived experiences, past to present. I thoroughly enjoyed this thought-provoking film which transcends genre and subverts colonial and ethnographic accounts of Aboriginal women.

References

Moffat, T. (Producer/Director). (1987). Nice coloured girls [Motion picture]. Australia: Women’s Film Fund and Australian Film Commission.

Moffatt, T. (1988). Changing images: An interview with Tracey Moffatt. Kunapipi, 10(1), 147-157. https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi/vol10/iss1/13

Senzani, A. (2007). Dreaming back: Tracey Moffatt’s bedevilling films. Essays in Film and the Humanities (27)1, 50-72.