Directed by: Jamie Coates (2018)

Film Length: 47:52

Intimate; Japan; China; Documentary; Culture; Music

Link: https://boap.uib.no/index.php/jaf/article/view/1538/1319

Jamie Coates’ 2018 documentary following the life of Chinese musicians in Japan offers an intimate glimpse into the nuances of friendship and what it means to find success. The titular word: pengyou, is defined in the first few minutes of the film as meaning friendship in Mandarin, revealing the theme that will preside over the next fifty minutes. The documentary follows the central figure of Dongshi over the course of four years. Dongshi, a Chinese musician in his late twenties with an aptitude for classical music but a passion for rock and roll; experiences ups and downs in his journey to find success in Japan. We “start at the end” with Dongshi reflecting on his experiences in Japan, his failing company, and his feelings towards his past naive self – we then go backwards in time and see some of the events he was discussing as they take place – before revisiting that same older, more jaded Dongshi at the end. Throughout the film, the viewer sees Dongshi navigating his personal relationships, the beginnings of his company, and some of his live performances – all centred around a music club called Turando in Tokyo’s unofficial Chinatown: Ikebukuro.

For a film about music, director Jamie Coates is very careful about where and how much music he puts in. He forgoes playing background music and instead uses natural sounds and amplifies them, such as the sound of the rain, background conversations, and the noises of the streets. This adds to the intimacy present in the film, as the viewer merely feels like an observer to the surroundings. When there is music, it is often music that is being sung live, or an instrument being played by Dongshi. This reflects not only how passionate the group is about their work, but also by keeping the music solely centred around the musicians – it makes the music shine even more in these revealing moments.

This documentary is filmed in a hand-held style, with the camera shakily following the action. The viewer is very much “walking along” as Dongshi goes to karaoke with friends, sits in his room, or is at Turando. In some cases, this kind of filming may be considered distracting, but in actuality, it works here to make the whole film feel intimate and accessible. Coates himself is almost never seen or heard, but his presence is acknowledged consistently. In one scene, Dongshi pulls Coates in for a hug, or in another Dongshi is drinking with friends and they insist the director partakes in a cheers. The viewer does not see him from behind the camera – instead only seeing his beer glass raised in front of the lens as they cheer and clink their drinks together. There is a constant emphasis on Dongshi’s relationships with others. The director often shows him with his friends, or surrounded by people in Ikebukuro. Dongshi very rarely looks into the camera, instead looks past it to whoever is behind. A few times he refers to the director directly by his name, Jamie, and ignores the camera entirely. In these moments, the viewer gets the sense that the director and Dongshi are friends, and in many ways along for this journey together. This is then coupled with more formal sit-down interviews using a steady cam to offer in-depth glimpses into how Dongshi came to be in Japan, his meeting and friendship with his company partner Huangkai, and his dreams. During these interviews Dongshi serves as an engaging and personable main focus, and easily keeps the viewer engaged as he recounts his life experiences.

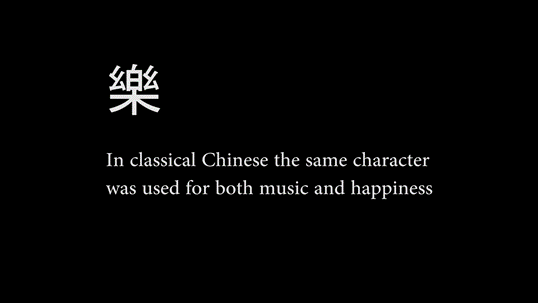

This emotional journey is coupled with black screens that transition into new time periods and scenes with a short phrase that relates to what will then be shown or provides context as to what has happened since. For instance, at 26:43 a black screen is flashed with the phrase, “In classical Chinese the same character was used for both music and happiness.” and then the scene begins with Dongshi discussing his start in music, and how his deep love for it has grown over the years. By the end of the film, the viewer feels invested in the story of Dongshi. Throughout, nothing shines through more than the genuine devotion and passion that radiates through Dongshi as he discusses his work amongst his friends, and that is the image that Jamie Coates is able to translate through his camera work and storytelling. At the basis of it: this is a story about a man doing what he loves to the best of his ability, and meeting the people he loves along the way.