Title of documentary: Lowland Kids

Director: Sandra Winther

Year: 2019

Length: 22 minutes

Keywords: Loss; Climate change; Family; Indigenous; Siblings; Home; Adolescence; Resilience

Link to watch the movie: https://www.shortoftheweek.com/2020/05/08/lowland-kids/

“What are you gonna miss about this place?” Juliette asks her brother, as dusk illuminates their figures running across the wetland. “Everything, man”, Howard answers solemnly.

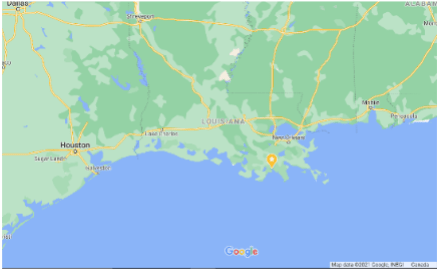

In her film “Lowland Kids”, Sandra Winther, a Danish filmmaker based in New York, captures the essence of adolescence and the importance of family and community. The backdrop of the film is an island whose very existence is doomed by rising sea levels and climate change. Isle de Jean Charles is home to the Indigenous band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw, accessible by a single road that is frequently flooded by hurricanes, cutting the residents off from the rest of the world. The island itself is disappearing rapidly – the Louisiana wetlands are losing a football field size of land every hour – a result partly due to canal dredging and other intensive practices employed by the oil and gas industries. The movie does not comment much on the issues of climate change although it is disrupting the community. Rather, this expository film focuses on painting a picture of the close-knit family coming to terms with having to leave the island in a few years, under the government-mandated relocation program.

The film’s participants are Howard Brunet, a driven and reserved 17-year-old football player, and Juliette Brunet, an outgoing and genuine 15-year-old, who are parented by their loving and hilarious uncle Chris, having lost their biological parents to drug overdose. Mike, Chris’s long-time friend, is also considered family and spends time hanging out and boating with them.

The film’s significant events are Chris’s birthday celebration in their backyard, a storm thundering through the area, and a trip to the lot on the mainland where the new houses will be built. Rather than events leading the film, Winther focuses on dialogue – the participant’s interactions and interviews. Intertitles are used in the movie sparingly to introduce the four participants by name and give context to the voiceovers. Winther intersperses voiceovers of interviews with the four individuals throughout the film. In addition to giving the viewer a closer look at the family’s dynamic, this technique provides an effortless and engaging rhythm. The frequent use of short voiceovers that alternate between participants gives an interesting effect, almost as if they are finishing each others’ sentences. Also, archival materials and recent news clips are used to show how much the wetlands have sunk over the years, giving a sense of urgency to the film.

Winther constructs the story by using many long shots throughout the movie, often of the island’s nature using drone footage, and close ups of the participants enjoying each others’ company in the outdoors. The long shots in the peaceful surroundings help us see how special these moments are, and how few of them are left to experience. The Brunets are already grieving the home they will soon lose – a unique place where people have belonged for many generations. The longer shots also give the audience time to absorb and reflect on the story being told. In contrast, lighthearted scenes are generally filmed with quicker, non-introspective cuts and include people outside of the family.

The slightly melancholy, meditative music, with lots of space between the notes, enhances the long shots, and made me feel immersed in the movie and empathize with the family. There is a turning point in the movie where a storm strikes, and the music responds by becoming rapid, ominous, and electronic, emphasizing the destructive and powerful forces acting upon the island.

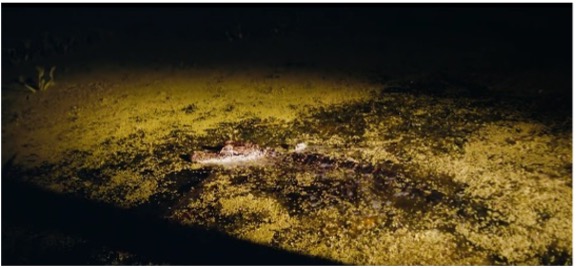

Many of the scenes are shot at dusk and in the night, and I found this particularly fascinating because it gives us a contemplative feeling about the island; the relationship between a person and their environment is not static. A poignant scene is when Mike talks about the parents’ addiction, and how Chris became Juliette and Howard’s role model and parent. Mike’s voiceover is paired with a magical scene of him on the boat with Juliette and Howard at night, shining a flashlight at the water and looking for alligators. The lights shine and the fireflies dance around in the sky as the light fades in and out. In this powerful scene I think the filmmaker uses the light and dark on screen as a metaphor for the light and dark in life itself. The awful event of losing their parents is outshone by the bright spot that is Chris, who supplies them stability and love.

Compared to other ethnographic films I have seen so far, I expected Winther to take on a more activist role. I was left wishing for a more critical response towards the societal structures that have allowed the effects of climate change to disproportionately affect this Indigenous group. The Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw tribe “settled the Island in the early 1800s, having been pushed into “uninhabitable” lands by European settler colonialism, slavery, and social inequality” (Comardelle, 2020), but this fact wasn’t mentioned at all. I think it would have been relevant to include, given that the tribe is still not having its needs met concerning the resettlement plan.

Perhaps this film’s main goal was to provide a reminder of how resilient and important family is, and that climate change is affecting human lives and cultures. Like Mike says at 18:47, “you can move your body but your heart’s home.” I laughed and cried watching and rewatching this film, and I hope you will all enjoy it!

Read more about Isle De Jean Charles from an Indigenous persepective

Watch the trailer on Vimeo

Follow the movie’s Instagram here

Check out the movie’s website here

References

Comardelle, C. (2020). Preserving Our Place: Isle de Jean Charles. Nonprofit Quarterly. Retrieved 26 February 2021, from https://nonprofitquarterly.org/preserving-our-place-isle-de-jean-charles/.

Google. Isle de Jean Charles and surrounding area [Image]. Retrieved 22 February 2021, from https://www.google.com/maps/@30.6912109,-91.241611,6z.

The Island — Isle de Jean Charles, Louisiana. Isle de Jean Charles, Louisiana. Retrieved 24 February 2021, from https://www.isledejeancharles.com/island. USGS: Louisiana’s Rate of Coastal Wetland Loss Continues to Slow. Usgs.gov. (2017). Retrieved 22 February 2021, from https://www.usgs.gov/news/usgs-louisiana-s-rate-coastal-wetland-loss-continues-slow